The emotional pulse of protest: Why people stand up against injustices

3 November 2025

Her research explores the emotional journey of activists, especially within climate movements. ‘Protest is not just a response to crisis, it is also a pathway to meaning and connection’, Anna Sach affirms.

Why protest? Three psychological drivers

At the heart of protests lies a powerful combination of thoughts and feelings. Sach elaborates that protest participation is driven by three key psychological ingredients.

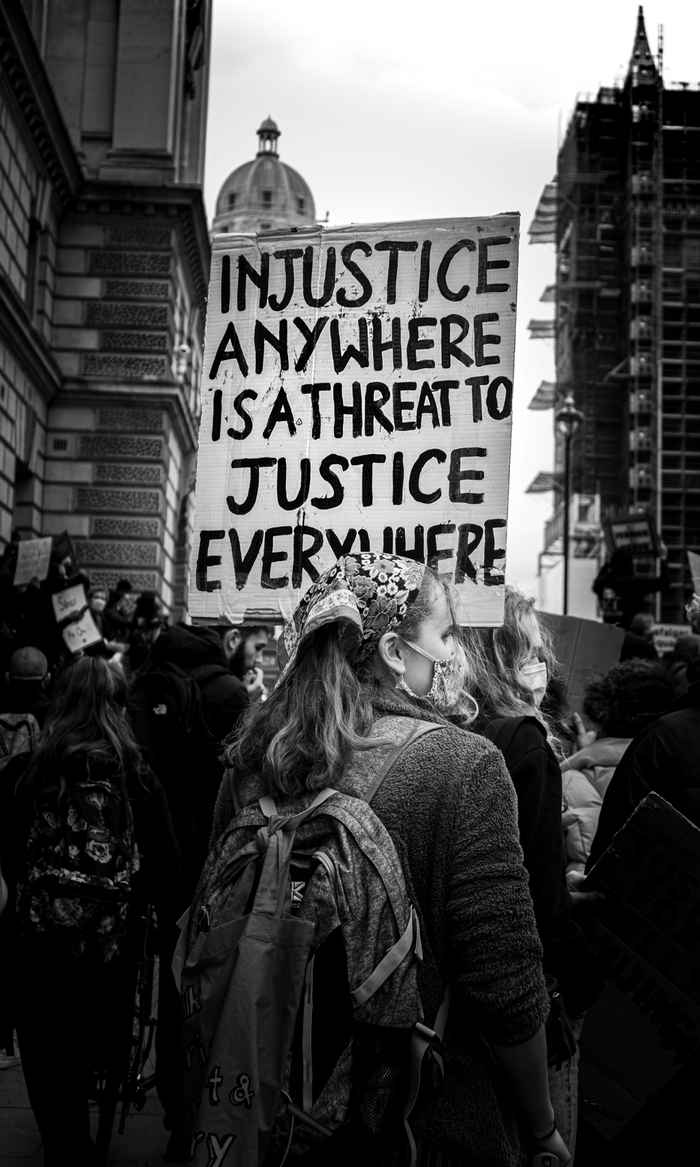

Injustice

The first is a strong sense of injustice. ‘People feel something is going wrong in the world, and that triggers a sense of moral urgency,’ says Sach. ‘This emotional and moral discomfort creates the initial spark that motivates people to act and participate in a protest.’

Belief that you can change something

The second ingredient is the belief that change is possible, either through their individual participation in collective action or together as a movement. ‘Protesters do not only feel concerned, they feel capable. You need to feel that you can make a change: you as a person, or as a group,’ Sach explains. ‘Without this sense of efficacy, people may feel despair rather than motivation.’

Identification

The third driver is identification. People join protests not only because they believe in a cause, but because they see themselves as part of a community that shares their values. ‘This identification, whether with a climate justice group, the Pro-Palestine movement, a human rights coalition or a peace organisation, creates a sense of closeness to others and shared values. Emotional connection is crucial for sustaining long-term engagement,’ Sach notes.

Emotions as the engine of activism

Sach expounds that protesting is an emotional journey. ‘Anger is one of the most common starting points. It arises from witnessing injustice and fuels the determination to act. But once people are participating, a range of other emotions come into play: hope for change, admiration for fellow activists, compassion for those affected and joy about feeling part of a collective.’

‘People collectively experience joy, they shout together, sing together, and make music,’ Sach explains. ‘These collective emotions are powerful drivers of long lasting engagement.’

The emotional impact of participation

Engaging in protest has significant emotional effects in the moment, but the effects of engagement can also last far beyond the event. Research demonstrates that participation in social movements can increase self-confidence, strengthen political identity and even influence major life decisions. ‘Protesters may become more outspoken, choose careers linked to social justice or reorient daily habits toward their values. We see that protest participation can change how people design their lives, what they do and where they work,’ she says.

From first-time protesters to experienced activists

Sach shows in her research that first-time protesters often report feeling nervous or uncertain about how to behave, what to say or how they will be perceived. Yet they also describe intense feelings of excitement and belonging.

Interestingly, She also has found that these emotional reactions are often stronger in newcomers than in experienced activists. ‘Over time, protesters may still feel committed, but the emotional intensity of joining a demonstration can lessen as participation becomes part of everyday life.’

By mapping the emotional journey from activists, she hopes to better understand what keeps people engaged or makes them disengage.

Protest as a force for emotional connection

‘Protest is not only a tool for political change, it is a deeply human experience that fulfils emotional and social needs. It creates community, restores a sense of agency and offers hope in the face of uncertainty. Protesting can give you community, connection, joy and the feeling of being effective,’ Sach concludes.